My blog, at least on the surface, is directed by reason and ruled by rationale. While I sometimes stray from the formula (see my occasional dabblings in annual Academy Awards season, etc.), I attempt to methodically determine what is the next best thing to post in conjunction with what has already been posted and what I would like to post in the near- and distant-future. In this regard, the option for my next film review is obvious: I’ve done three Hitchcock films and three Coppola films (Vertigo, Notorious, Psycho, The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, and The Conversation) and only two silent films (The General and Battleship Potemkin). It is time, therefore, for a silent film. Continue reading

Category Archives: Reviews

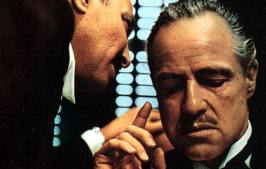

The Conversation (1974)

Coppola’s most celebrated films are the first two Godfather movies. The first came out in 1972, and the second came out at the end of 1974. In between them, there was The Conversation. The Conversation has lost much of his reputation and prestige over the last two generations or so, and that is a great misfortune for such a quality film, which played quality role in Coppola’s complete compendium. The reason for this importance is simple: it is Coppola’s most personal, introverted film, in other words, it his most revealing auteur picture. Understanding the context of auteurism improves the overall viewing experience of The Conversation. Continue reading

Psycho (1960)

You’ll hopefully notice the patterns. We’re on our third Hitchcock-Coppola-Silent Film cycle. We also just did a ten-thousand word analysis (complete with pictures) on montage theory. Now, we will do a review on the “mother” of all Hitchcock films, one that includes the “mother” of all film montages. Why is Psycho the “mother” of all Hitchcock films? For those who have seen the film, the use of that word as qualifier is perfect. This is most famous Hitchcock, containing some of the most iconic images and characters and featuring the most recognizable music. Is it the best? No. Vertigo is. But this film is certainly among his best. While most movie critics decry its popularity because, while it is definitely a five-star film, Hitchcock has other five-star films that deserve more credit—like Notorious, Rebecca, or Rear Window. However, I think it deserves its place. My mood often changes, and it is most appropriate to say these films are all tied for first; but if you made me pick, Psycho would have to follow Vertigo if only for its cultural clout and haunting storyline. It sticks with you, perhaps more than any other Hitchcock film (except Vertigo, but that holds far too many trump cards, and if I keep bringing it up, it will succeed in boxing out Psycho from its own review). The whole nature of the film is haphazard, like a good haunted house, full of eery sounds, precipitous pictures, and a whole bunch of mentally-troubled characters. Its very origin cries out its rawness. Continue reading

Battleship Potemkin (1925)*

*And supplementary lecture on the nature of silent film.

This blog is due for another silent film, and the one that I have selected is Battleship Potemkin (or, in Russian, Bronenosyets Potyomkin). As was recently posted, Potemkin stands at number 2 on my list of the “Most Important Films of All Time.” These are films selected strictly for aesthetic and technical innovation, with the qualification that said innovation produced radical change in the popular movie landscape, and not due to story or tertiary film elements along the lines of score, acting, or literary devices—save for those situations when one of those tertiary elements brought forth radical change (Wizard of Oz, for example). These were, quite simply, decided upon the film itself. Not the film as in “the movie,” but film as in the film, the literal celluloid collection. Embracing film as a singular art medium is a necessary facet to understanding silent films, and is unfortunately lost in much of what we consider quality film criticism today. Continue reading

Apocalypse Now (1979)

My structure remains. Hitchcock, Coppola, silent film. Hitchcock, Coppola, silent film. Hitchcock, Coppola, silent film. Perhaps after that, I’ll move on to other things. As for Coppola, The Godfather movies provide only so much potency. What The Godfather enjoyed, perhaps to a greater degree than any other movie was that it was a story so stunning–and so driven by motif and character–that it probably could have made itself. Put a director with Francis Ford Coppola’s touch behind the camera and the movie no longer makes itself, but instead becomes the most precious clay a sculptor could ever want: a clay that becomes a masterpiece by mixing the perfection of the plot with the tenacious and dexterous master’s touch. With that being said, there is perhaps no Coppola film that better exhibits the directorial skill of its creator than 1979’s Apocalypse Now. Continue reading

Notorious (1946)

In light of my most recent posts listing the best actors and acting performances in film, alongside a two-part page series on the analysis of acting, it is only timely to kill two birds with one stone. Bird number one: write my next review–which is supposed to be on a Hitchcock film as the framework for my blog requires. Bird number two: write a supplementary article on a superb acting performance within the context of a single film. Stone number one and only: Notorious. Continue reading

The General (1927)

I hope I timed this well. I stated in my review of The Godfather that certain movies are better than others for the novice movie-watcher in order to springboard into the finer world of film. I said that Hitchcock films, Coppola films, and silent films all fit that regulatory bill. Other films are also fitting, but for consistency’s sake, and for structure’s sake, I stated those three categories. I intend to keep to my aforementioned schedule so as to not confuse anyone, and also so I don’t have to backtrack and edit old comments due to my own lack of foresight. We have a Hitchcock movie and a Coppola movie under our belt already. Now, it’s time for a silent film. Continue reading

The Godfather (1972)

There is a somewhat calculated way that I go about selecting which films I want to review first, and I do it in accordance with what my imaginary audience would deem most useful. If my true goal is to highlight the progression from casual to competent–and I believe that I have made that expressly clear–it would not be wise of me to jump into a review of L’Avventura or The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. What I have found to be the best springboards for development as an active movie-watcher are any Hitchcock film, most Coppola films, and, surprisingly, silent movies. I hope to use these three sub-groups in my preliminary reviews. Continue reading

Vertigo (1958)

Alfred Hitchcock is considered by many voices in the industry to be the greatest director of all time. It suffices to say that I agree with these voices. For so many of us, Hitchcock represents the stunning collaborative effect of art, technique, and personality—a personality that was as complex as it was singularly driven; his self-awareness only heightening the depths to which he allowed himself to operate. He has several stand-out films that define these many different facets of his personality. Rear Window tackles the horrors of obsession and handicap. Rebecca deals with the concept of haunting ghosts and tainted love. Notorious challenges the cliches of a love affair and asks how far is one really willing to go to prove their devotion. Psycho provides sheer terror and mental complexes, while Frenzy takes those to a new level before the backdrop of overt sexuality and social tension. Dial “M” for Murder and Rope conquer the issues of a “perfect murder” and the moral relationship–and supposed ambiguity–of death and killing. North by Northwest and The 39 Steps make evident to the greatest degree the patented Hitchcock-ian humor and wit. The Birds, like so many others, gives the viewer an iconic motif that will never be forgotten. Sabotage and the Man Who Knew Too Much films deal with the horror of a murdered of endangered loved one. Spellbound demonstrates the brilliance of artistic expression to terrify in its surrealist embrace of the subconscious. Shadow of a Doubt and The Lady Vanishes permeate us with the actuality of what life is like when we are alone and are in very real danger–even when the threat is only perceived. At the end of the day, watching a Hitchcock film is more an exploration of self than one would realize at first blush: he was as much an auteur as he was an exhibitionist, as much a psychoanalyst as he was a showman. Continue reading